Question 1. Discuss the applicability of Rolle’s Theorem for the following functions on the indicated intervals:

(i) f(x) = 3 + (x – 2)2/3 on [1, 3]

Solution:

Rolle’s theorem states that if a function f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and

differentiable on the open interval (a, b) such that f(a) = f(b), then f′(x) = 0 for some x with a ≤ x ≤ b.

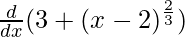

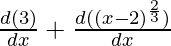

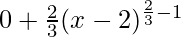

We have, f'(x) =

⇒ f'(x) =

⇒ f'(x) =

⇒ f'(x) =

To analyse differentiability at x = 2:

⇒ f'(2) = ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [\frac{2}{3(2-2)}]^{\frac{1}{3}}](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-b9cfa97827fe14c82aa92d4575f37cd0_l3.png)

= 2 / 0 ≠ 0

Since f'(2) ≠ 0, f(x) is not differentiable in the interval [1, 3].

Hence, the Rolle’s Theorem is not applicable for the given function f(x) in interval [1, 3].

(ii) f(x) = [x] for -1 ≤ x ≤ 1, where [x] denotes the greatest integer not exceeding x

Solution:

Rolle’s theorem requires a function to be continuous on the closed interval [a, b].

The continuity of f(x) needs to be analyzed at x = 1:

(RHL at x = 1) = limx⇢(1+h)[x]

= limh⇢0[1 + h]

= 1 ….. (1)

(LHL at x = 1) = limx⇢(1-h)[x]

= limh⇢0[1 – h]

= 0 …… (2)

Since f(x) is not continuous at x = 1 or the interval [-1, 1].

Hence, the Rolle’s Theorem is not applicable for the given function f(x) in interval [-1, 1].

(iii) f(x) = sin(1/x) for -1 ≤ x ≤ 1

Solution:

Rolle’s theorem requires a function to be continuous on the closed interval [a, b].

The continuity of f(x) needs to be analyzed at x = 0:

(RHL at x = 0) = limx⇢(0+h)sin(1/x)

= limh⇢0sin(1/h)

= k …..(1)

(LHL at x = 0) = limx⇢(0-h)sin(1/x)

= limh⇢0sin(1/0-h)

= limh⇢0sin(-1/h)

= -limh⇢0sin(1/h)

= −k ….(2)

Since f(x) is not continuous at x = 1 or the interval [-1,1].

Hence, the Rolle’s Theorem is not applicable for the given function f(x) in interval [-1, 1].

(iv) f(x) = 2x2 – 5x + 3 on [1, 3]

Solution:

Clearly f(x) being a polynomial function shall be continuous on the interval.

We need to verify whether f(a) = f(b) for the applicability of theorem.

Here, f(1) = 2(1)2 – 5(1) + 3

⇒ f(1) = 2 – 5 + 3

⇒ f(1) = 0 …… (1)

Now, f(3) = 2(3)2 – 5(3) + 3

⇒ f(3) = 2(9) – 15 + 3

⇒ f(3) = 18 – 12

⇒ f(3) = 6 …… (2)

From eq(1) and (2), we can say that, f(1) ≠ f(3).

We observe that f(a) ≠ f(b)

Hence, the Rolle’s Theorem is not applicable for the given function f(x) in interval [1, 3].

(v) f (x) = x2/3 on [-1, 1]

Solution:

Rolle’s theorem states that if a function f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and

differentiable on the open interval (a, b) such that f(a) = f(b), then f′(x) = 0 for some x with a ≤ x ≤ b.

f'(x) =

⇒ f'(x) =

Clearly f'(x) is undefined at x = 0.

Hence, the Rolle’s Theorem is not applicable for the given function f(x) in interval [-1, 1].

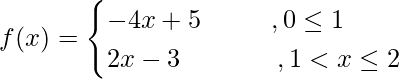

(vi)

Solution:

Rolle’s theorem requires a function to be continuous on the closed interval [a, b].

The continuity of f(x) needs to be analyzed at x = 1:

(LHL at x = 1) = lim(x->1-h) (-4x + 5)

= lim(h->0) [-4(1 – h) + 5]

= -4 + 5

= 1

(RHL at x = 1) = lim(x->1+h) (2x – 3)

= lim(h->0) [2(1 + h) – 3]

= 2(0) – 3

= -1

We observe that LHL ≠ RHL.

Clearly f(x) is not continuous at x = 1.

Hence, the Rolle’s Theorem is not applicable for the f(x) function in interval [-1, 1].

Question 2. Verify the Rolle’s Theorem for each of the following functions on the indicated intervals:

(i) f (x) = x2 – 8x + 12 on [2, 6]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = x2 – 8x + 12 on [2, 6].

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere i.e., on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

Thus, f(2) = 22 – 8(2) + 12

⇒ f(2) = 4 – 16 + 12

⇒ f(2) = 0

Now, f(6) = 62 – 8(6) + 12

⇒ f(6) = 36 – 48 + 12

⇒ f(6) = 0

Since f(2) = f(6), Rolle’s theorem is applicable for function f(x) on [2, 6].

f(x) = x2 – 8x + 12

f'(x) = 2x – 8

Then f'(c) = 0

2c – 8 = 0

c = 4 ∈ (2, 6)

Hence, the Rolle’s theorem is verified

(ii) f(x) = x2 – 4x + 3 on [1, 3]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = x2 – 4x + 3 on [1, 3]

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere i.e., on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (1) = 12 – 4(1) + 3

⇒ f (1) = 1 – 4 + 3

⇒ f (1) = 0

Now, f (3) = 32 – 4(3) + 3

⇒ f (3) = 9 – 12 + 3

⇒ f (3) = 0

∴ f (1) = f(3), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function ‘f’ on [1, 3].

⇒ f’(x) = 2x – 4

We have f’(c) = 0, c ϵ (1, 3), from the definition of Rolle’s Theorem.

⇒ f’(c) = 0

⇒ 2c – 4 = 0

⇒ 2c = 4

⇒ c = 4/2

⇒ c = 2 ∈ (1, 3)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(iii) f (x) = (x – 1) (x – 2)2 on [1, 2]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = (x – 1) (x – 2)2 on [1, 2]

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere that is on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (1) = (1 – 1) (1 – 2)2

⇒ f (1) = 0(1)2

⇒ f (1) = 0

Now, f (2) = (2 – 1)(2 – 2)2

⇒ f (2) = 02

⇒ f (2) = 0

Since f (1) = f (2), Rolle’s Theorem applicable for function f(x) on [1, 2].

f(x) = (x – 1)(x – 2)2

f'(x) = (x – 1) × 2(x – 2) + (x – 2)2

f'(x) = (x – 2) (3x – 4)

Then f'(c) = 0

(c – 2)(3c – 4) = 0

c = 2

or

c = 4/3 ∈ (1, 2)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(iv) f (x) = x (x – 1)2 on [0, 1]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = x(x – 1)2 on [0, 1]

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere that is, on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (0) = 0 (0 – 1)2

⇒ f (0) = 0

Now f (1) = 1 (1 – 1)2

⇒ f (1) = 02

⇒ f (1) = 0

Since f (0) = f (1), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function f(x) on [0, 1].

f (x) = x (x – 1)2

f'(x) = (x – 1)2+ x × 2(x – 1)

= (x – 1)(x – 1 + 2x)

= (x – 1)(3x – 1)

Then f'(c) = 0

(c – 1)(3c – 1) = 0

c = 1 or 1/3 ∈ (0, 1)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(v) f (x) = (x2 – 1) (x – 2) on [-1, 2]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = (x2 – 1) (x – 2) on [– 1, 2]

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere that is on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f(–1) = (( – 1)2 – 1)( – 1 – 2)

⇒ f ( – 1) = (1 – 1)( – 3)

⇒ f ( – 1) = (0)( – 3)

⇒ f ( – 1) = 0

Now, f (2) = (22 – 1)(2 – 2)

⇒ f (2) = (4 – 1)(0)

⇒ f (2) = 0

∴ f (– 1) = f (2), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function f on[ – 1, 2].

⇒ f’(x) = 3x2 – 4x – 1

We have f’(c) = 0 c ∈ (-1, 2), from the definition of Rolle’s Theorem.

Clearly, f'(c) = 0

3c2 – 4c – 1 = 0

c = (2 ±√7)/ 3

c = 1/3(2 + √7) or 1/3(2 – √7) ∈ (-1, 2)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(vi) f(x) = x(x – 4)2 on [0, 4]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = x(x – 4)2 on [0, 4]

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere i.e., on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (0) = 0(0 – 4)2

⇒ f (0) = 0

Now, f (4) = 4(4 – 4)2

⇒ f (4) = 4(0)2

⇒ f (4) = 0

Since f (0) = f (4), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function f(x) on [0, 4].

f(x) = x(x – 4)2

f'(x) = x × 2(x – 4) + (x – 4)2

= 2x2 – 8x + x2 + 16 – 8x

= 2x2 – 16x + 16

Then

f'(c) = 2c2 – 16c + 16

= (c – 4)(3c – 4)

c = 4 or 4/3 ∈ (0, 4)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(vii) f (x) = x(x – 2)2 on [0, 2]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = x(x – 2)2 on [0, 2].

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere that is on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (0) = 0(0 – 2)2

⇒ f (0) = 0

Now, f (2) = 2(2 – 2)2

⇒ f (2) = 2(0)2

⇒ f (2) = 0

f (0) = f(2), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function f on [0,2].

c = 12/6 or 4/6

c = 2 or 2/3

So, c = 2/3 since c ∈ (0, 2)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(viii) f (x) = x2 + 5x + 6 on [-3, -2]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = x2 + 5x + 6 on [– 3, – 2].

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere i.e., on R.

We only need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f(–3) = (–3)2 + 5(–3) + 6

⇒ f(–3) = 9 – 15 + 6

⇒ f(–3) = 0

Now, f(–2) = (–2)2 + 5(–2) + 6

⇒ f(–2) = 4 – 10 + 6

⇒ f(–2) = 0

Since f(–3) = f(–2), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function f(x) on [–3, –2].

f(x) = x2 + 5x + 6

f'(x) = 2x + 5

Then

f(c) = 0

2c + 5 = 0

c = -5/2 ∈ (-3, -2)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

Question 3. Verify the Rolle’s Theorem for each of the following functions on the indicated intervals:

(i) f(x) = cos2(x – π/4) on [0, π/2]

Solution:

Clearly the cosine function is continuous and differentiable everywhere.

Hence, the given function f(x) is continuous in [0, π/2] and differentiable in [0, π/2]

So,

f(0) = cos2(0 – π/4) = 0

f(π/2) = cos2(π/2 – π/4) = 0

Since f(0) = f(π/2), Rolle’s theorem applicable for function f(x) on [0, π/2].

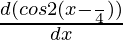

Now, f'(x) =

= -2sin(2x – π/2)

If f'(c) = 0

⇒ -2sin(2c – π/2) = 0

⇒ c = π/4 ∈ [0, π/2]

Clearly c belongs to the given interval.

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified.

(ii) f(x) = sin 2x on [0, π/2]

Solution:

Since sin 2x is everywhere continuous and differentiable.

So, sin2x is continuous on (0, π/2) and differentiable on (0, π/2).

f(0) = sin 0 = 0

f(π/2) = sin π/2 = 0

f(π/2) = f(0) = 0

Thus, f(x) satisfies all the conditions of Rolle’s theorem.

Now, we have to show that there exists c in (0, π/2) such that f'(c) = 0.

We have, f'(x) = 0

⇒ cos2x = 0

⇒ x = π/4

So, f'(c) = 2cos2c

2cos2c = 0

Thus, c = π/4 in (0, π/2).

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified.

(iii) f(x) = cos2x on [-π/4, π/4]

Solution:

Since cos 2x is everywhere continuous and differentiable.

So, cos2x is continuous on [-π/4, π/4] and differentiable on [-π/4, π/4].

cos(-π/4) = cos2(-π/4) = cos(-π/2) = 0

cos(π/4) = cos2(π/4) = cos(π/2) = 0

Also, cos(-π/4) = cos(π/4)

Thus, f(x) satisfies all the conditions of Rolle’s theorem.

Now, we have to show that there exists c in (0, π/2) such that f'(c) = 0.

We have f'(x) = 0

⇒ sin2c = 0

⇒ 2c = 0

So, c = 0 as c ∈ (-π/4, π/4)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(iv) ex sin x on [0, π]

Solution:

The given function is a composition of exponential and trigonometric functions. Hence it is differential and continuous everywhere.

So, the given function f(x) is continuous on [0, π] and differentiable on (0, π).

f(0) = e0 sin 0 = 0

f(π) = eπ sin π = 0

f(0) = f(π)

Now, we have to show that there exists c in (0, π) such that f'(c) = 0.

So f'(x) = ex (sin x + cos x)

⇒ ex (sin x + cos x) = 0

⇒ sin x + cos x = 0

Dividing both sides by cos x, we have

tan x = -1

⇒ x = π – π/4 = 3π/4

Since c = 3π/4 in (0, π) such that f'(c) = 0.

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(v) f(x) = ex cos x on [−π/2, π/2]

Solution:

The given function is a composition of exponential and trigonometric functions. Hence it is differential and continuous everywhere.

So, the given function f(x) is continuous on [-π/2, π/2] and differentiable on (-π/2, π/2).

f(−π/2) = eπ/2 cos(−π/2) = 0

f(π/2) = eπ/2 cos(π/2) = 0

f(−π/2) = f(π/2)

Now, we have to show that there exists c in (-π/2, π/2) such that f'(c) = 0.

f'(x) = ex (cos x – sin x)

⇒ ex (cos x – sin x) = 0

⇒ sin x – cos x = 0

Dividing both sides by cos x, we have

tan x = 1

⇒ x = π/4

Since c = π/4 in (-π/2, π/2) such that f’(c) = 0.

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(vi) f (x) = cos 2x on [0, π]

Solution:

Since cos 2x is everywhere continuous and differentiable.

So, cos2x is continuous on [0, π] and differentiable on (0, π).

f(0) = cos(0) = 1

f(π) = cos(2π) = 1

f(0) = f(π)

Thus, f(x) satisfies all the conditions of Rolle’s theorem.

There must be a c belongs to (0, π) such that f’(c) = 0.

⇒ sin 2c = 0

So, 2c = 0 or π

c = 0 or π/2

But, c = π/2 as c ∈ (0, π)

Hence, Rolle’s Theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(vii) f(x) = sinx/ex on 0 ≤ x ≤ π

Solution:

The given function is a composition of exponential and trigonometric functions.

Hence it is differential and continuous everywhere.

So, sinx/ex is continuous on [0, π] and differentiable on (0, π).

f(0) = sin(0)/e0 = 0

f(π) = sin(π)/eπ = 1

f(0) = f(π)

Now, we have to show that there exists c in (0, π/2) such that f'(c) = 0.

f'(x) = ex (cos x – sin x)

⇒ ex (cos x – sin x) = 0

⇒ sin x – cos x = 0

⇒ tan x = 1

⇒ x = π/4

Since c = π/4 in (-π/4, π/4) such that f’(c) = 0.

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(viii) f(x) = sin 3x on [0, π]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = sin3x on [0, π]

Since sine function is continuous and differentiable on R.

We need to check whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (0) = sin 3(0)

⇒ f (0) = sin0

⇒ f (0) = 0

Now, f (π) = sin 3π

⇒ f (π) = sin(3 π)

⇒ f (π) = 0

We have f (0) = f (π), so there exist a c belongs to (0, π) such that f’(c) = 0.

⇒ 3cos(3x) = 0

⇒ cos 3x = 0

⇒ 3x = π / 2

⇒ x = π / 6 ∈ [0, π]

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(ix) f(x) =  on [−1, 1]

on [−1, 1]

Solution:

We know that the exponential function is continuous and differentiable everywhere.

So,  is continuous on [-1, 1] and differentiable on (-1, 1).

is continuous on [-1, 1] and differentiable on (-1, 1).

f(-1) = e1-1 = 1

f(1) = e1-1 = 1

Also, f(-1) = f(1) = 1

Thus, Rolle’s theorem is applicable. So there must exist c ∈ [−1, 1] such that f'(c) = 0.

f'(x) = ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com -2x [e^{1 - x^2}]](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-13d83976bb86a3a63ef5efea06798ac8_l3.png)

⇒ -2x e^{1 – x^2} = 0

⇒ x = 0 ∈ [−1, 1]

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified.

(x) f (x) = log (x2 + 2) – log 3 on [-1, 1]

Solution:

Clearly the logarithmic function is continuous and differentiable in its own domain.

We need to verify whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (– 1) = log((– 1)2 + 2) – log 3

⇒ f (– 1) = log (1 + 2) – log 3

⇒ f (– 1) = log 3 – log 3

⇒ f ( – 1) = 0

Now, f (1) = log (12 + 2) – log 3

⇒ f (1) = log (1 + 2) – log 3

⇒ f (1) = log 3 – log 3

⇒ f (1) = 0

We have got f (– 1) = f (1).

So, there exists a c such that c ϵ (– 1, 1) such that f’(c) = 0.

Now, f'(x) =

f'(c) = 0

⇒ c = 0 ϵ (– 1, 1)

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified.

(xi) f(x) = sin x + cos x on [0, π/2]

Solution:

Since sin and cos functions are continuous and differentiable everywhere,

f(x) is continuous on [0, π/2] and differentiable on (0, π/2).

So, f(0) = sin 0 + cos 0 = 1

f(π/2) = sin π/2 + cos π/2 = 1

Also, f(0) = f(π/2) = 1.

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is applicable. So there must exist c ∈ [−1, 1] such that f'(c) = 0.

Now, f'(x) = cos x – sin x

⇒ cos x – sin x = 0

⇒ tan x = 1

⇒ x = π/4

Thus, c = π/4 on (0, π/2).

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(xii) f (x) = 2 sin x + sin 2x on [0, π]

Solution:

Since sin function continuous and differentiable over R, f(x) is continuous on [0, π] and differentiable on (0, π).

We need to verify whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (0) = 2sin(0) + sin2(0)

⇒ f (0) = 2(0) + 0

⇒ f (0) = 0

Now, f (π) = 2sin(π) + sin2(π)

⇒ f (π) = 2(0) + 0

⇒ f (π) = 0

We have f (0) = f (π), so there exist a c belongs to (0, π) such that f’(c) = 0.

f'(x) = 2cos x + cos 2x

Now, f'(c) = 0

⇒ 2cos x + cos 2x = 0

⇒ (2cos c – 1) (cos c + 1) = 0

⇒ tan c = 1

⇒ c = π/3 in (0, π)

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(xiii) f(x) = ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \frac{x}{2} - \sin[\frac{\pi x}{6}]](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-6ca6d37d4bb2b8131b8b7b24f8513044_l3.png) on [-1, 0]

on [-1, 0]

Solution:

Since sin function is continuous and differentiable over R, f(x) is continuous on [-1, 0] and differentiable on (-1, 0).

f(-1) = ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \frac{-1}{2} - \sin[\frac{\pi (-1)}{6}]](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-062a475861b19ab68016bddbc864df21_l3.png) = 0

= 0

f(0) = 0 – sin 0 = 0

Also f(-1) = f(0) = 0

Hence Rolle’s theorem is applicable so there exist a c belongs to (0, π) such that f’(c) = 0.

f'(x) = ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \frac{1}{2} - \frac{\pi}{6}\cos[\frac{\pi x}{6}]](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e215a918dec976bec3cfc2ea03d3d5df_l3.png)

Now, f'(c) = 0

⇒ ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \frac{1}{2} - \frac{\pi}{6}\cos[\frac{\pi c}{6}] = 0](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-dc3d64edb18767c5347e19640a33bb49_l3.png)

⇒

⇒ c = ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com (\frac{- 6}{\pi}) \cos^{- 1} [\frac{3}{\pi}]](https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c8d91d3bbf1722ee933290b7b056ab7c_l3.png)

Thus, c ϵ (-1, 0).

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

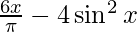

(xiv) f(x) =  on [0, π/6]

on [0, π/6]

Solution:

Since sin function is continuous and differentiable everywhere, f(x) is continuous on [0, π/6] and differentiable on (0, π/6).

f(0) = 0 – 0 = 0

f(π/6) = 1 – 1 = 0

Also, f(0) = f(π/6) = 0

Hence Rolle’s theorem is applicable so there exist a c belongs to (0, π/6) such that f’(c) = 0.

We have, f'(x) = 6/π – 8sinxcosx

f'(x) = 6/π – 4sin2x

f'(c) = 0

6/π – 4sin2c = 0

4sin2c = 6/π

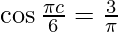

sin2c = 3/2π

2c = sin-1(21/44)

c = 1/2 sin-1(21/44)

c ∈ (-1/2, 1/2)

c ∈ (0, 11/21)

c ∈ (0, π/6)

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(xv) f(x) = 4sin x on [0, π]

Solution:

Since sin and exponential functions are continuous and differentiable everywhere, f(x) is continuous on [0, π] and differentiable on (0, π).

f(0) = 4sin 0 = 1

f(π) = 4sin π = 1

Also, f(0) = f(π) = 1.

Hence Rolle’s theorem is applicable so there exist a c belongs to (0, π) such that f’(c) = 0.

We have, f'(x) = 4sin x cos x log 4

So, f’(c) = 0

4sin c cos c log 4 = 0

4sin c cos c = 0

cos c = 0

c = π/2 ∈ (0, π)

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(xvi) f (x) = x2 – 5x + 4 on [1, 4]

Solution:

Since, given function f is a polynomial it is continuous and differentiable everywhere i.e., on R.

We need to verify whether f(a) = f(b) or not.

So f (1) = 12 – 5(1) + 4

⇒ f (1) = 1 – 5 + 4

⇒ f (1) = 0

Now, f (4) = 42 – 5(4) + 4

⇒ f (4) = 16 – 20 + 4

⇒ f (4) = 0

We have f (1) = f (4). So, there exists a c ∈ (1, 4) such that f’(c) = 0.

f'(x) = 2x – 5

Now, f'(c) = 2c – 5 = 0

Thus, c = 5 / 2 ∈ (1, 4).

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified for the given function f(x).

(xvii) f(x) = sin4 x + cos4 x on (0, π/2)

Solution:

Since sin and cos functions are continuous and differentiable everywhere, f(x) is continuous on [0, π/2] and differentiable on (0, π/2).

So,

f(0) = sin4(0) + cos4(0) = 1

f(π/2) = sin4(π/2) + cos4(π/2) = 1

f(0) = f(π/2)

Hence Rolle’s theorem is applicable so there exist a c belongs to (0, π/2) such that f’(c) = 0.

⇒ f'(x) = 4sin3 x cos x – 4cos3 x sin x

so, f'(c) = 4sin3 x cos x – 4cos3 x sin x = 0

4sin3 c cos c – 4cos3 c sin c = 0

-sin4c = 0

4x = 0 or 4x = π

x = 0, or π/4 ∈ (0, π/2)

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified.

(xviii) f(x) = sin x – sin 2x on [0, π]

Solution:

Given function is f (x) = sin x – sin2x on [0, π]

We know that sine function is continuous and differentiable over R.

Now we have to check the values of the function ‘f’ at the extremes.

⇒ f (0) = sin (0) – sin 2(0)

⇒ f (0) = 0 – sin (0)

⇒ f (0) = 0

⇒ f (π) = sin(π) – sin2(π)

⇒ f (π) = 0 – sin(2π)

⇒ f (π) = 0

We have f (0) = f (π). So, there exists a c ∈ (0, π) such that f’(c) = 0.

f'(x) = cos x – 2cos 2x

so, f'(c) = 0

f'(c) = cos c – 2cos 2c = 0

cos c – (2cos2c + 1) = 0

2cos2 c – cosc – 1 = 0

(cos c – 1)(2cos c + 1) = 0

cos c = 1, -1/2

c = cos(π/2), cos(2π/3)

So, c = π/2, 2π/3 ∈ (0, π)

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is verified.

Question 4. Using Rolle’s Theorem, find points on the curve y = 16 – x2, x ∈ [-1, 1], where the tangent is parallel to the x-axis.

Solution:

Given: y = 16 – x2, x ϵ [– 1, 1]

⇒ y (– 1) = 16 – (– 1)2

⇒ y (– 1) = 16 – 1

⇒ y (– 1) = 15

Now, y (1) = 16 – (1)2

⇒ y (1) = 16 – 1

⇒ y (1) = 15

We have y (– 1) = y (1). So, there exists a c ϵ (– 1, 1) such that f’(c) = 0.

We know that for a curve g, the value of the slope of the tangent at a point r is given by g’(r).

⇒ y’ = –2x

We have y’(c) = 0

⇒ – 2c = 0

⇒ c = 0 ϵ (– 1, 1)

Value of y at x = 1 is

⇒ y = 16 – 02

⇒ y = 16

Hence, the point at which the curve y has a tangent parallel to x – axis (since the slope of x – axis is 0) is (0, 16).

Question 5. At what points on the following curves is the tangent parallel to the x-axis?

(i) y = x2 on [-2, 2]

Solution:

Given: f(x) = x2

f'(x) = 2x

Also, f(-2) = f(2) = 22 = (-2)2 = 4

So, there exists a c ϵ (-2, 2) such that f’(c) = 0.

⇒ 2c = 0

⇒ c = 0

Therefore the required point is (0, 0).

(ii) y =  on [−1, 1]

on [−1, 1]

Solution:

Since exponential function is continuous and differentiable everywhere.

Here f(1) = f(-1) = 1

Thus, all the conditions of Rolle’s theorem are satisfied.

Consequently, there exists at least one point c in (-1, 1) for which f'(c) = 0.

⇒ f'(c) = 0

⇒ -2c e^{1 – c^2} = 0

⇒ c = 0

Hence, (0, e) is the required point.

(iii) y = 12 (x + 1) (x − 2) on [−1, 2]

Solution:

Since polynomial function is continuous and differentiable everywhere.

Here f(2) = f(-1) = 0.

Thus, all the conditions of Rolle’s theorem are satisfied.

Consequently, there exists at least one point c in (-1, 2) for which f'(c) = 0.

But f'(c) = 0

⇒ 24c – 12 = 0

⇒ c = 1/2

Hence, (1/2, -27) is the required point.

Question 6. If f: [5, 5] to R is a differentiable function and if f'(x) does not vanish anywhere, prove that f(-5) ≠ f(5).

Solution:

Here f(x) is differentiable on (5,5).

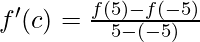

By Mean Value Theorem,

⇒ 10 f'(c) = f(5) – f(-5)

It is also given that f'(x) does not vanish anywhere.

⇒ f'(c) ≠ 0

⇒ 10 f'(c) ≠ 0

⇒ f(5) – f(-5) ≠ 0

⇒ f(5) ≠ f(-5)

Hence Proved

Question 7. Examine if Rolle’s theorem is applicable to any one of the following functions.

(i) f (x) = [x] for x ∈ [5, 9]

(ii) f (x) = [x] for x ∈ [−2, 2]

Can you say something about the converse of Rolle’s Theorem from these functions?

Solution:

Rolle’s theorem states that if a function f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and differentiable on the open interval (a, b) such that f(a) = f(b), then f′(x) = 0 for some x with a ≤ x ≤ b.

(i) f(x) = [x] for x ∈ [ 5 , 9 ]

f(x) is not continuous at x = 5 and x = 9. Thus, f (x) is not continuous on [5, 9].

Also , f (5) = [5] = 5 and f (9) = [9] = 9

∴ f (5) ≠ f (9)

The left hand limit of f at x = n is ∞ and the right hand limit of f at x = n is 0.

Since the left and the right hand limits of f at x = n are not equal, f is not differentiable on (5, 9).

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is not applicable on function f(x) for x ∈ [5 , 9].

(ii) f (x) = [x] for x ∈ [-2 , 2]

f(x) is not continuous at x = −2 and x = 2. Thus, f (x) is not continuous on [−2, 2].

Also, f (-2) = [-2] = -2 and f (2) = [2] = 2

∴ f (-2) ≠ f (2)

The left hand limit of f at x = n is ∞ and the right hand limit of f at x = n is ∞.

Since the left and the right hand limits of f at x = n are not equal, thus, f is not differentiable on (−2, 2).

Hence, Rolle’s theorem is not applicable on function f(x) = [x] for x ∈ [ -2, 2].

Share your thoughts in the comments

Please Login to comment...