Database security refers to the collective measures used to protect a database management system from malicious threats and unauthorized access. In simple terms, it’s making sure that only the right people can get to your data, and that the data stays accurate and available. This includes

- Use strong passwords and enforce rotation/MFA.

- Control user permissions with least privilege (grant only what’s needed).

- Encrypt sensitive data at rest and in transit.

- Keep regular backups and test restores.

- Aim for CIA: confidentiality (no leaks), integrity (no tampering), availability (no downtime).

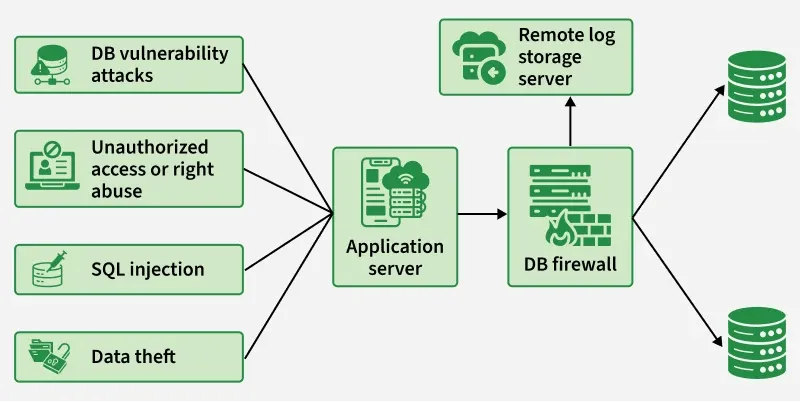

Example: Your databases hold the crown jewels—customer records, finances, credentials. If attackers slip in, you’re staring at data theft, privacy breaches, and brand damage. The diagram shows those risks (SQL injection, vuln exploits, privilege abuse, data exfiltration) hitting the app server.

To avoid a repeat of “exposed DB” wipe-and-ransom incidents, all traffic is funneled through a DB firewall that inspects and blocks suspicious queries and enforces policy, while a remote log server captures tamper-resistant audit trails for investigation. Clean traffic proceeds to the databases.

Common Database Attack Methods

Below are some of the most common database attack methods (from basic to advanced) and what they mean:

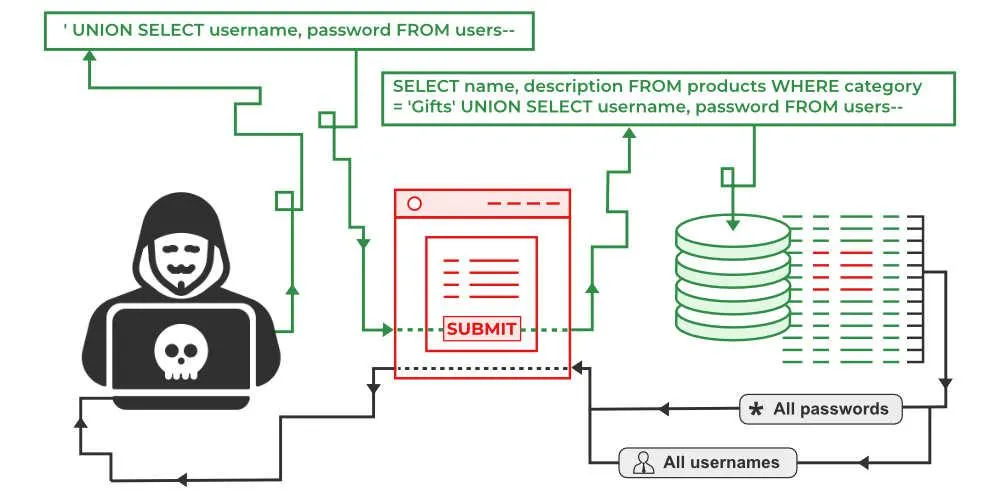

SQL Injection (SQLi) – This is the number one threat to web databases. It happens when an attacker “injects” malicious SQL code into a query (usually via a web form input) to manipulate the database. For example, they might trick your database into giving away all user data by always making a condition true. (We’ll explain an example in the next section.) SQL injection can allow attackers to bypass logins, steal or delete data, or even take over the entire database.

Weak Authentication & Brute-Force – If your database accounts use default or weak passwords, attackers can simply guess or brute-force their way in. Brute-force attacks involve trying many passwords until one works. Not having account lockouts or using common passwords makes this easy for hackers.

Privilege Abuse (Insider Threat) – Sometimes the danger comes from legitimate users abusing their access. If a user’s account has more privileges than necessary, they might misuse data. For example, a salesperson allowed to view individual customer records might run a query to export all customer data and sell it to a competitor.

Database Misconfiguration – An unsecured configuration can be an open door. For instance, installing a database and leaving it with default settings (default user accounts, no encryption, open network ports) is dangerous. Many cloud databases by default listen on all network interfaces and may be open to the internet if not locked down

Example: How SQL Injection Works

Suppose your application checks a username and password like this (in pseudocode SQL):

-- Insecure example of a login query (vulnerable to SQLi)

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = 'admin' AND password = 'password';

The above query is fine if the inputs are legitimate. But if the application directly inserts whatever the user types (without validation or parameterization), an attacker can input special SQL code to change the query. For instance, a hacker could enter the following as the username:

' OR '1'='1

And leave the password blank. The application might then construct a query like:

-- Malicious input modifies the query logic

SELECT * FROM users

WHERE username = '' OR '1'='1' --' AND password = '';

- Attacker input: '' OR '1'='1' --

- Original intent: SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='<input>' AND password='<input>';

- Injected query (effectively): ... WHERE username='' OR '1'='1' -- AND password='...'

- -- comment: everything after it is ignored (the password check is skipped).

- Condition evaluated: username='' OR '1'='1' → always true because '1'='1'.

- Result: the WHERE clause matches, authentication is bypassed.

Control methods of Database Security

Database security control methods include strong authentication, role-based authorization (least privilege), encryption at rest/in transit, auditing/logging, network access controls (firewalls/VPC), and backups with tested restores.

- Use Strong Authentication and Access Control

- Principle of Least Privilege (LoP)

- Secure Configuration and Hardening

- Keep Your Database Software Up-to-Date

- Enable Encryption for Data in Transit and at Rest

- Backup Your Database Regularly (and Secure the Backups)

For example, imagine an attacker somehow obtains a read-only account’s password. If you followed least privilege, that account can’t modify or dump all data. If you have monitoring, you might catch the unusual activity. If encryption is enabled, the stolen data might be useless without keys. If you have backups, even a ransomware attack that wipes your database can be recovered. It’s all about stacking the odds in your favor.

Cloud Database Security in DBMS

Cloud database security (DBMS) relies on a shared-responsibility model using IAM-based access, network isolation (VPC/private endpoints), encryption at rest/in transit (KMS/CMKs), auditing/monitoring, automated backups/DR, and compliance controls. It provides:

- Shared responsibility: provider secures infra; you secure data, identities, configs.

- Strong IAM: least-privilege roles, MFA, short-lived creds; rotate keys/secrets.

- Network isolation: VPC/private subnets, SGs/NACLs, private endpoints (no public IPs).

- Encryption: at rest (KMS/CMKs) and in transit (TLS); manage key rotation.

- Secrets management: store DB creds in a vault (Secrets Manager/HashiCorp).

- Backups & DR: automated backups, PITR, cross-region replicas; test restores.

- Patching & hardening: managed services auto-patch; disable unused features/ports.

- Audit & monitoring: DB logs, CloudTrail/CloudWatch alerts, anomaly detection, SIEM.

Explore

Basics of DBMS

ER & Relational Model

Relational Algebra

Functional Dependencies & Normalisation

Transactions & Concurrency Control

Advanced DBMS

Practice Questions