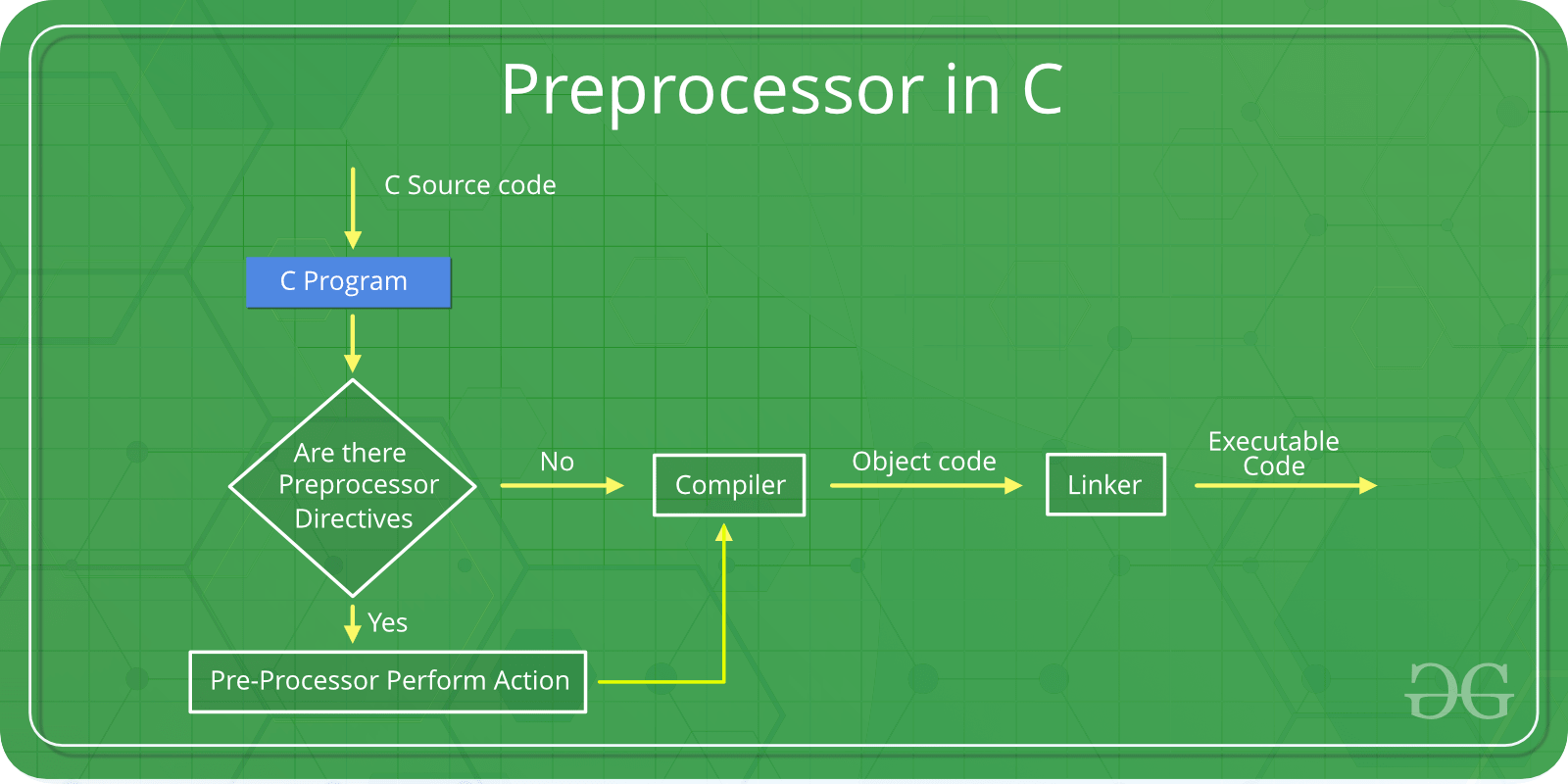

Preprocessors are programs that process the source code before compilation. Several steps are involved between writing a program and executing a program in C. Let us have a look at these steps before we actually start learning about Preprocessors.

You can see the intermediate steps in the above diagram. The source code written by programmers is first stored in a file, let the name be “program.c“. This file is then processed by preprocessors and an expanded source code file is generated named “program.i”. This expanded file is compiled by the compiler and an object code file is generated named “program.obj”. Finally, the linker links this object code file to the object code of the library functions to generate the executable file “program.exe”.

Preprocessor Directives in C

Preprocessor programs provide preprocessor directives that tell the compiler to preprocess the source code before compiling. All of these preprocessor directives begin with a ‘#’ (hash) symbol. The ‘#’ symbol indicates that whatever statement starts with a ‘#’ will go to the preprocessor program to get executed. We can place these preprocessor directives anywhere in our program.

Examples of some preprocessor directives are: #include, #define, #ifndef, etc.

Note Remember that the # symbol only provides a path to the preprocessor, and a command such as include is processed by the preprocessor program. For example, #include will include the code or content of the specified file in your program.

List of preprocessor directives in C

The following table lists all the preprocessor directives in C:

|

#define

|

Used to define a macro |

|

#undef

|

Used to undefine a macro |

|

#include

|

Used to include a file in the source code program |

|

#ifdef

|

Used to include a section of code if a certain macro is defined by #define |

|

#ifndef

|

Used to include a section of code if a certain macro is not defined by #define |

|

#if

|

Check for the specified condition |

|

#else

|

Alternate code that executes when #if fails |

|

#endif

|

Used to mark the end of #if, #ifdef, and #ifndef |

These preprocessors can be classified based on the type of function they perform.

Types of C Preprocessors

There are 4 Main Types of Preprocessor Directives:

- Macros

- File Inclusion

- Conditional Compilation

- Other directives

Let us now learn about each of these directives in detail.

1. Macros

In C, Macros are pieces of code in a program that is given some name. Whenever this name is encountered by the compiler, the compiler replaces the name with the actual piece of code. The ‘#define’ directive is used to define a macro.

Syntax of Macro Definition

#define token value

where after preprocessing, the token will be expanded to its value in the program.

Example of Macro

C

#include <stdio.h>

#define LIMIT 5

int main()

{

for (int i = 0; i < LIMIT; i++) {

printf("%d \n", i);

}

return 0;

}

|

In the above program, when the compiler executes the word LIMIT, it replaces it with 5. The word ‘LIMIT’ in the macro definition is called a macro template and ‘5’ is macro expansion.

Note There is no semi-colon (;) at the end of the macro definition. Macro definitions do not need a semi-colon to end.

There are also some Predefined Macros in C which are useful in providing various functionalities to our program.

Macros With Arguments

We can also pass arguments to macros. Macros defined with arguments work similarly to functions.

Example

#define foo(a, b) a + b

#define func(r) r * r

Let us understand this with a program:

C

#include <stdio.h>

#define AREA(l, b) (l * b)

int main()

{

int l1 = 10, l2 = 5, area;

area = AREA(l1, l2);

printf("Area of rectangle is: %d", area);

return 0;

}

|

Output

Area of rectangle is: 50

We can see from the above program that whenever the compiler finds AREA(l, b) in the program, it replaces it with the statement (l*b). Not only this, but the values passed to the macro template AREA(l, b) will also be replaced in the statement (l*b). Therefore AREA(10, 5) will be equal to 10*5.

2. File Inclusion

This type of preprocessor directive tells the compiler to include a file in the source code program. The #include preprocessor directive is used to include the header files in the C program.

There are two types of files that can be included by the user in the program:

Standard Header Files

The standard header files contain definitions of pre-defined functions like printf(), scanf(), etc. These files must be included to work with these functions. Different functions are declared in different header files.

For example, standard I/O functions are in the ‘iostream’ file whereas functions that perform string operations are in the ‘string’ file.

Syntax

#include <file_name>

where file_name is the name of the header file to be included. The ‘<‘ and ‘>’ brackets tell the compiler to look for the file in the standard directory.

User-defined Header Files

When a program becomes very large, it is a good practice to divide it into smaller files and include them whenever needed. These types of files are user-defined header files.

Syntax

#include "filename"

The double quotes ( ” ” ) tell the compiler to search for the header file in the source file’s directory.

3. Conditional Compilation

Conditional Compilation in C directives is a type of directive that helps to compile a specific portion of the program or to skip the compilation of some specific part of the program based on some conditions. There are the following preprocessor directives that are used to insert conditional code:

- #if Directive

- #ifdef Directive

- #ifndef Directive

- #else Directive

- #elif Directive

- #endif Directive

#endif directive is used to close off the #if, #ifdef, and #ifndef opening directives which means the preprocessing of these directives is completed.

Syntax

#ifdef macro_name

// Code to be executed if macro_name is defined

#ifndef macro_name

// Code to be executed if macro_name is not defined

#if constant_expr

// Code to be executed if constant_expression is true

#elif another_constant_expr

// Code to be excuted if another_constant_expression is true

#else

// Code to be excuted if none of the above conditions are true

#endif

If the macro with the name ‘macro_name‘ is defined, then the block of statements will execute normally, but if it is not defined, the compiler will simply skip this block of statements.

Example

The below example demonstrates the use of #include #if, #elif, #else, and #endif preprocessor directives.

C

#include <stdio.h>

#define PI 3.14159

int main()

{

#ifdef PI

printf("PI is defined\n");

#elif defined(SQUARE)

printf("Square is defined\n");

#else

#error "Neither PI nor SQUARE is defined"

#endif

#ifndef SQUARE

printf("Square is not defined");

#else

cout << "Square is defined" << endl;

#endif

return 0;

}

|

Output

PI is defined

Square is not defined

4. Other Directives

Apart from the above directives, there are two more directives that are not commonly used. These are:

- #undef Directive

- #pragma Directive

1. #undef Directive

The #undef directive is used to undefine an existing macro. This directive works as:

#undef LIMIT

Using this statement will undefine the existing macro LIMIT. After this statement, every “#ifdef LIMIT” statement will evaluate as false.

Example

The below example demonstrates the working of #undef Directive.

C

#include <stdio.h>

#define MIN_VALUE 10

int main() {

printf("Min value is: %d\n",MIN_VALUE);

#undef MIN_VALUE

#define MIN_VALUE 20

printf("Min value after undef and again redefining it: %d\n", MIN_VALUE);

return 0;

}

|

Output

Min value is: 10

Min value after undef and again redefining it: 20

2. #pragma Directive

This directive is a special purpose directive and is used to turn on or off some features. These types of directives are compiler-specific, i.e., they vary from compiler to compiler.

Syntax

#pragma directive

Some of the #pragma directives are discussed below:

- #pragma startup: These directives help us to specify the functions that are needed to run before program startup (before the control passes to main()).

- #pragma exit: These directives help us to specify the functions that are needed to run just before the program exit (just before the control returns from main()).

Below program will not work with GCC compilers.

Example

The below program illustrate the use of #pragma exit and pragma startup

C

#include <stdio.h>

void func1();

void func2();

#pragma startup func1

#pragma exit func2

void func1() { printf("Inside func1()\n"); }

void func2() { printf("Inside func2()\n"); }

int main()

{

void func1();

void func2();

printf("Inside main()\n");

return 0;

}

|

Expected Output

Inside func1()

Inside main()

Inside func2()

The above code will produce the output as given below when run on GCC compilers:

Inside main()c

This happens because GCC does not support #pragma startup or exit. However, you can use the below code for the expected output on GCC compilers.

C

#include <stdio.h>

void func1();

void func2();

void __attribute__((constructor)) func1();

void __attribute__((destructor)) func2();

void func1()

{

printf("Inside func1()\n");

}

void func2()

{

printf("Inside func2()\n");

}

int main()

{

printf("Inside main()\n");

return 0;

}

|

Output

Inside func1()

Inside main()

Inside func2()

In the above program, we have used some specific syntaxes so that one of the functions executes before the main function and the other executes after the main function.

#pragma warn Directive

This directive is used to hide the warning message which is displayed during compilation. We can hide the warnings as shown below:

- #pragma warn -rvl: This directive hides those warnings which are raised when a function that is supposed to return a value does not return a value.

- #pragma warn -par: This directive hides those warnings which are raised when a function does not use the parameters passed to it.

- #pragma warn -rch: This directive hides those warnings which are raised when a code is unreachable. For example, any code written after the return statement in a function is unreachable.

If you like GeeksforGeeks and would like to contribute, you can also write an article using write.geeksforgeeks.org. See your article appearing on the GeeksforGeeks main page and help other Geeks. Please write comments if you find anything incorrect, or if you want to share more information about the topic discussed above.

Like Article

Suggest improvement

Share your thoughts in the comments

Please Login to comment...